“If you don’t know where you are going, you’ll end up someplace else.”

— Yogi Berra

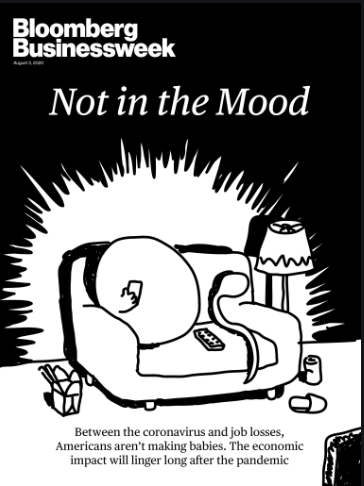

I just received my copy of Bloomberg Businessweek (yes, I’m the one who still gets it in physical form!).

The cover article, “Not in the Mood,” explains that for the most part, since the start of the pandemic, Americans are not making babies.

Early on, some had predicted just the opposite — expecting a baby boom similar to what we’ve sometimes seen in the past when couples were unable to leave the house.

Imagine, now, that you are a crib manufacturer, trying to anticipate demand for the next few years. Or an automaker, unsure how much manufacturing capacity to allocate to minivans. In both examples (and countless others), a baby boom or a baby bust can have far-reaching — even existential — implications for your business.

That’s where “scenario planning” comes in. First applied to business strategy in the 1970s by Shell Oil Company as it anticipated how decisions by OPEC might impact worldwide oil supply and pricing, this strategic tool allows organizations to plan for uncertain future outcomes.

So, what is scenario planning? Well, here’s what it’s not…

It’s not the tired old approach that anyone who’s ever developed multi-year budgets in a corporate setting has used — the kind where you make your future financial projections based on one set of assumptions, and then create an “optimistic” forecast based on revenues being 10% higher than the base case, and a “pessimistic” forecast based on them being 10% lower.

That’s fine as far as it goes. But it’s only useful to the extent that the future is very similar to the past, and that whatever happens occurs within a very narrow range of outcomes.

Scenario planning, by contrast, is a process of trying to envision a broad range of possible — often extremely diverse — outcomes (stories), from which you plan accordingly. Using our baby example from earlier, this isn’t “What if there is a 5% increase in births next year?” This is, “What if there is an 80% swing in either direction?”

Some things to keep in mind when developing scenarios…

Ask big questions.

The process begins by considering significant, often environmental factors that can have an impact.

What if there is political unrest in a country in which a major parts supplier operates?

What if demand for your services drops by half?

What if the current administration stays in power? What if it doesn’t?

What if most remote workers continue to work from home and don’t return to offices when it becomes safe to do so?

Develop two or three scenarios.

While you should begin by thinking about several different possibilities, you’ll ultimately want to narrow down the number you consider to just two or three that seem feasible. Evaluating too many can be overwhelming and limit your ability to move forward.

The goal is not to predict the future — it’s to envision possible situations that might leave you vulnerable or open up opportunities, so that you can consider how to prepare for unexpected situations.

Then, as time passes and relevant indicators begin to suggest which scenario is looking most likely, you can start taking the actions you had prepared for moving in that direction.

Identify elements that you can predict well.

Demographic trends are not hard to anticipate. For example, it’s easy to know how many 18-year-olds there will be five years from now. Universities have been aware of the coming decline and have been preparing for several years.

Likewise, while those in the health and human services fields don’t know how and when managed care may come to complex long term services and supports, they do know they’ll need to have better data gathering and managing capabilities in order to succeed when it does.

Identify elements that you can’t predict well.

For example, many large companies developed extensive and far-reaching supply chains over the past several years, relying on companies in multiple countries to coordinate efficiently and with just-in-time connections.

Companies that had prepared for a scenario where access to one or more of those countries might suddenly be interrupted, based on trade disputes or other factors, would have been better off today, even if they had not envisioned a global pandemic as the reason for the disruption.

Evaluate your internal capabilities and commitments.

Different future realities will require different responses. How well prepared are you?

For example, if telehealth, that was not very prevalent pre-COVID, keeps its current penetration at the 80+% range, how will you, as a healthcare provider, respond? What if, instead, insurance companies reduce payment levels for telehealth delivery once the pandemic is past, and penetration drops to 30-40%?

In these scenarios, you might consider the following questions: What lease commitments do we have? How easy would it be to reconfigure the space for current requirements (and reconfigure it again once the pandemic has passed)? What technology platform have we adopted and what improvements can we make to it? What cybersecurity procedures do we have in place? How are we positioned relative to our competition?

Steps you take today (or don’t) may dictate how prepared, flexible and ultimately successful you will be going forward.

Reflections

The future may be uncertain, but it’s a pretty safe bet that it won’t be a straight line from here to there.

Scenario planning, unlike its more traditional cousin, the multi-year budget, is a means of preparing for the extremes — both positive and negative. After all, it’s there where the greatest risks and opportunities lie.